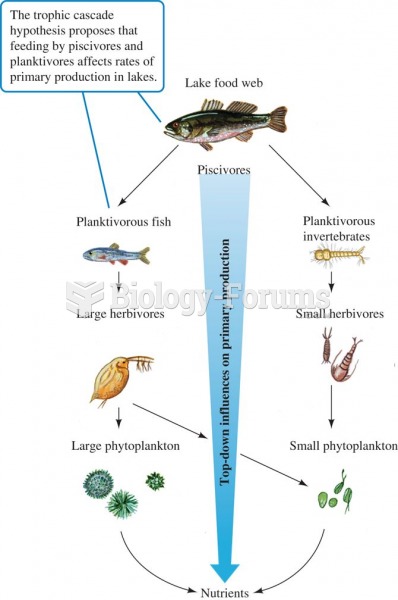

Definition for Trophic cascade

From Biology Forums Dictionary

The elimination of predators destabilizes ecosystems, setting off chain reactions that eventually cascade down the trophic ladder (food web pyramid) to the lowest rung, often reducing habitat complexity and species diversity.* In 1980, Paine coined the term “trophic cascade” to describe this process such multi-trophic level interactions. The altered state is less biodiverse and more simple.

The “Paine Effect” describes this loss of keystone predators and resultant degradation and species loss. Robert Paine famously removed a species of starfish from study plots on Washington’s coast and noted an unpredictably intense set of changes occur in his plots, which were quickly overtaken by mussels usually kept in check by the starfish.

A widely known example is provided by gray wolves in Yellowstone, where extirpation (local extinction) of this large carnivore led to an irruption in the numbers of elk, causing changes in vegetation structure, species composition, and diversity. Without wolves keeping these ungulates in check, elk achieved much higher densities and shifted their behavior to a more concentrated feeding pattern, leading to the virtual disappearance of major vegetation types such as aspen and willow-beaver wetlands in some areas. Once wolves were restored to the park, over-browsed vegetation was given a chance to recover and the park’s natural vegetative pattern began to return.

Another cascading pathway in Yellowstone is the wolves-coyotes-pronghorn antelope connection. In the absence of wolves, coyote numbers increased. Because coyotes are major predators on young antelope, the antelope population was reduced in the absence of wolves. When wolves returned, coyote numbers dropped by about 50 percent, followed by an increase in antelope numbers by about fifty percent. Large carnivores are not the only type of keystone species (remember the starfish example). Smaller examples include prairie dogs, flying squirrels, and sapsuckers.

Successful conservation of North America’s natural heritage requires us to preserve, and where necessary, reintroduce populations of keystone and other strongly interactive species. These species must be conserved at ecologically effective population numbers; i.e.,with enough abundance for the species to play the roles described above, versus a scattered handful of individuals that are largely symbolic. Protecting habitat is insufficient on its own. The habitats we conserve will unravel if they are not regulated by the full complement of native keystone and other strongly interactive species.