Definition for Paper chromatography

From Biology Forums Dictionary

Contents

[hide]Introduction

Chromatography is used to separate mixtures of substances into their components. All forms of chromatography work on the same principle.

They all have a stationary phase (a solid, or a liquid supported on a solid) and a mobile phase (a liquid or a gas). The mobile phase flows through the stationary phase and carries the components of the mixture with it. Different components travel at different rates. We'll look at the reasons for this further down the page.

In paper chromatography, the stationary phase is a very uniform absorbent paper. The mobile phase is a suitable liquid solvent or mixture of solvents.

Producing a paper chromatogram

You probably used paper chromatography as one of the first things you ever did in chemistry to separate out mixtures of coloured dyes - for example, the dyes which make up a particular ink. That's an easy example to take, so let's start from there.

Suppose you have three blue pens and you want to find out which one was used to write a message. Samples of each ink are spotted on to a pencil line drawn on a sheet of chromatography paper. Some of the ink from the message is dissolved in the minimum possible amount of a suitable solvent, and that is also spotted onto the same line. In the diagram, the pens are labelled 1, 2 and 3, and the message ink as M.

Note: The chromatography paper will in fact be pure white - not pale grey. I'm forced to show it as off-white because of the way I construct the diagrams. Anything I draw as pure white allows the background colour of the page to show through.

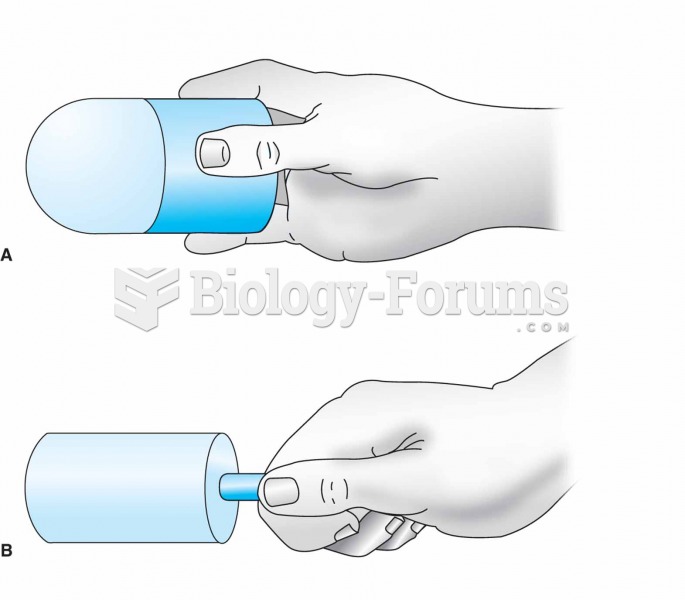

The paper is suspended in a container with a shallow layer of a suitable solvent or mixture of solvents in it. It is important that the solvent level is below the line with the spots on it. The next diagram doesn't show details of how the paper is suspended because there are too many possible ways of doing it and it clutters the diagram. Sometimes the paper is just coiled into a loose cylinder and fastened with paper clips top and bottom. The cylinder then just stands in the bottom of the container.

The reason for covering the container is to make sure that the atmosphere in the beaker is saturated with solvent vapour. Saturating the atmosphere in the beaker with vapour stops the solvent from evaporating as it rises up the paper.

As the solvent slowly travels up the paper, the different components of the ink mixtures travel at different rates and the mixtures are separated into different coloured spots.

The diagram shows what the plate might look like after the solvent has moved almost to the top.

It is fairly easy to see from the final chromatogram that the pen that wrote the message contained the same dyes as pen 2. You can also see that pen 1 contains a mixture of two different blue dyes - one of which might be the same as the single dye in pen 3.

Rf values

Some compounds in a mixture travel almost as far as the solvent does; some stay much closer to the base line. The distance travelled relative to the solvent is a constant for a particular compound as long as you keep everything else constant - the type of paper and the exact composition of the solvent, for example.

The distance travelled relative to the solvent is called the Rf value. For each compound it can be worked out using the formula:

For example, if one component of a mixture travelled 9.6 cm from the base line while the solvent had travelled 12.0 cm, then the Rf value for that component is:

In the example we looked at with the various pens, it wasn't necessary to measure Rf values because you are making a direct comparison just by looking at the chromatogram.

You are making the assumption that if you have two spots in the final chromatogram which are the same colour and have travelled the same distance up the paper, they are most likely the same compound. It isn't necessarily true of course - you could have two similarly coloured compounds with very similar Rf values. We'll look at how you can get around that problem further down the page.

What if the substances you are interested in are colourless?

In some cases, it may be possible to make the spots visible by reacting them with something which produces a coloured product. A good example of this is in chromatograms produced from amino acid mixtures.

Suppose you had a mixture of amino acids and wanted to find out which particular amino acids the mixture contained. For simplicity we'll assume that you know the mixture can only possibly contain five of the common amino acids.

A small drop of a solution of the mixture is placed on the base line of the paper, and similar small spots of the known amino acids are placed alongside it. The paper is then stood in a suitable solvent and left to develop as before. In the diagram, the mixture is M, and the known amino acids are labelled 1 to 5.

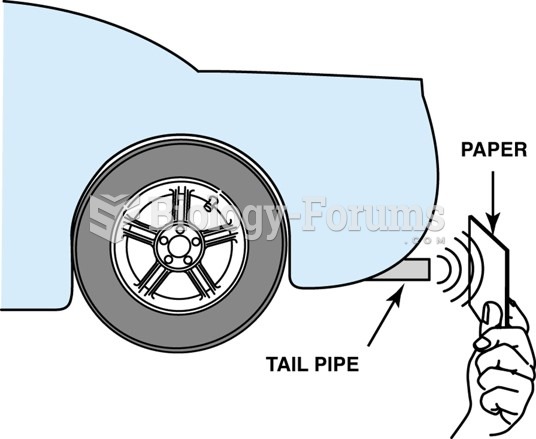

The position of the solvent front is marked in pencil and the chromatogram is allowed to dry and is then sprayed with a solution of ninhydrin. Ninhydrin reacts with amino acids to give coloured compounds, mainly brown or purple.

The left-hand diagram shows the paper after the solvent front has almost reached the top. The spots are still invisible. The second diagram shows what it might look like after spraying with ninhydrin.

There is no need to measure the Rf values because you can easily compare the spots in the mixture with those of the known amino acids - both from their positions and their colours.

In this example, the mixture contains the amino acids labelled as 1, 4 and 5.

And what if the mixture contained amino acids other than the ones we have used for comparison? There would be spots in the mixture which didn't match those from the known amino acids. You would have to re-run the experiment using other amino acids for comparison.